I‘ve been in three different innovation teams created by large organisations, in very different sectors, and they’ve all started and ended the same way.

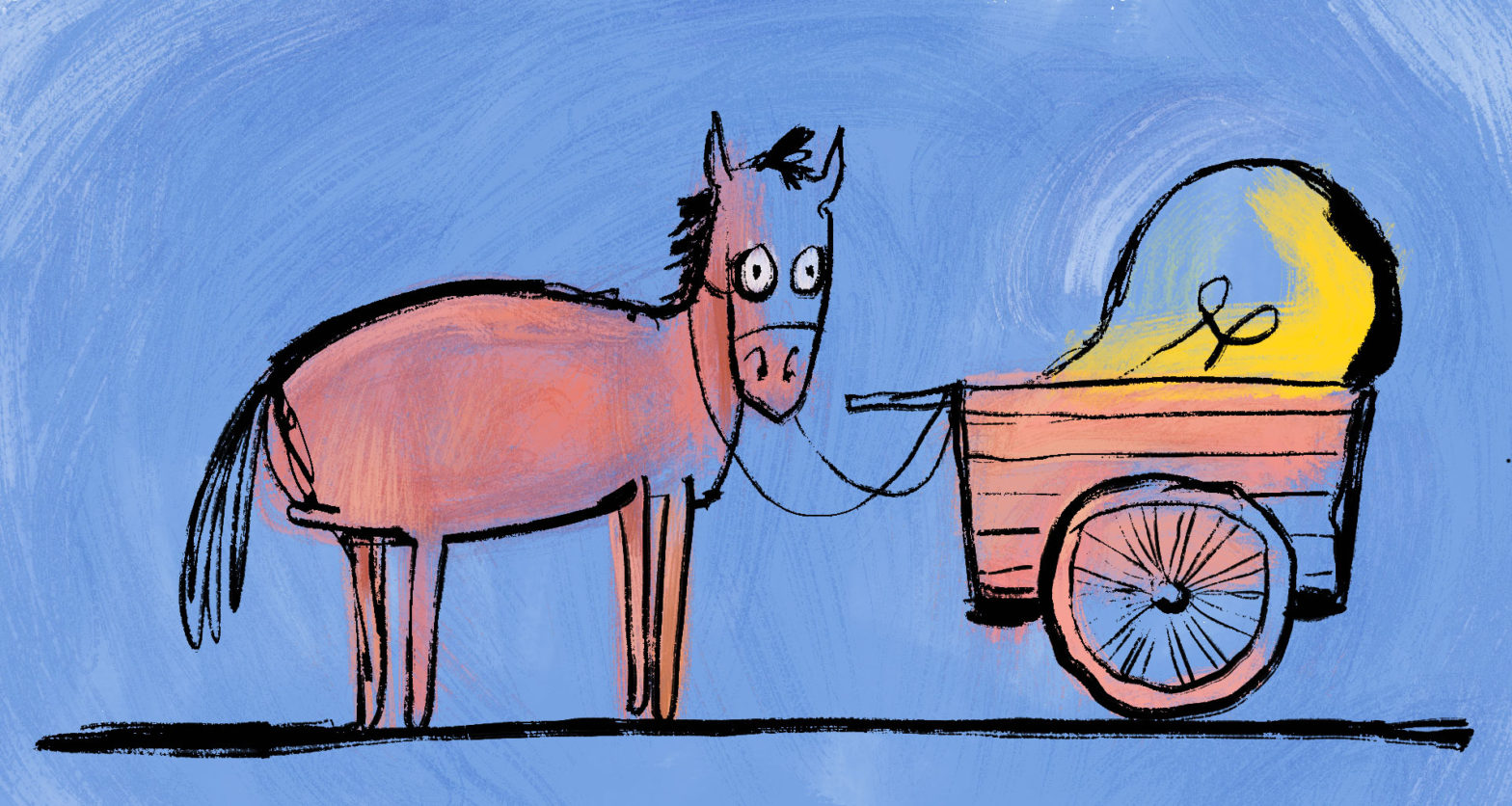

They start with a dream – we want to use our vast capital and resources to ‘start a start-up’ – to break free of the governance structures that slow down big organisations’ decision-making capability to move quickly to improve profit, people, and planet. And, they’ve all ended the same way – the market isn’t ready or not big enough for our innovative thinking and so the commercials don’t justify continued investment.

It’s a curious thing to witness. Three different teams. Three different organisations. Three very different types of tech. They only share one common characteristic – they all began with the technology and not the problem.

The problem with starting without a problem

Look, I get it, tech is exciting. Especially new tech. VR, AI, Web3 and blockchain – it’s all cutting edge stuff and it’s stuff that companies should have their eye on if they want to take advantage of it or defend themselves against possible disruption. I am all-in for exploring the possibilities of new and emerging technology to see when, how, or if it could be used to benefit the strategic goals of the businesses. It’s just – in my experience – it doesn’t seem to happen that way.

In each of the three innovation teams I’ve worked within it’s been the same story (simplified to make a point):

- Identify new or emerging tech

- Deploy engineers and a ‘head of innovation’ to explore it

- As they explore, they imagine ways the business could benefit

- Keep exploring further

- Repeat steps 3 and 4 until the money runs out

In this model, there is always a feeling of progress because what this model does is accelerate learning. And, when we’re learning, we feel we’re making progress. We feel as though we’re moving closer to the big imaginary lightbulb above someone’s head. We’re not sure towards what exactly we’ll arrive, but we feel arrival is imminent, so we keep going because we’ll know when we get there and ‘that’s what innovation is about’ (real quote, btw).

And, in many ways, I agree – these are all good things. I’m a big advocate of play for play’s sake. Of exploring without a purpose for a while to learn things that structured learning may not teach because of the limits imposed on it by boundaries that are inherent in structured learning. But the problem occurs when we’re constantly engaging in divergent thinking – wider and wider – without any sense of synthesis and reflection.

Alternative approaches to tech-led innovation

So, what to do? We want to enable play and exploration, but we also want it to unlock something for the organisation or the company, at some point or at various stages along the way. This is where innovation labs could benefit from either/or:

- Hypothesis-led testing and validation (aka. The Hare – Move fast and break things)

- Problem first, then solution second. (aka. The Tortoise – Move slow and fix things)

Hypothesis-led innovation

The methods that describe scientific exploration can be easily adapted to corporate innovation. The idea that one can postulate an outcome before beginning to explore it gives some really wide boundaries for innovation teams to play within. In other words, set a goal post in the far distance, then play and explore until we reach it. Then reflect. It’s not complicated. It’s not rocket science, it’s just science.

This isn’t reinventing the wheel, it’s just using the one that already exists, for many years, in academia and scientific research. It’s the structure that enables play, rather than restricts it. It’s also straight-forward:

—

- We believe that…

- To verify this, we will…

- And measure…

- We are right if…

—

So why is doing this well so difficult? What I’ve seen are four reasons:

- Not everyone is a scientist. Theories of change (of which hypothesis-led testing is one), fall over quickly because of people’s under-developed logic skills. Things like circular logic, and a magical belief in actions/tactics because of bias and assumptions.

- The change or ‘vision’ is multi-variant. It’s easy to compare change when you tweak 1 thing against another, but tweaking 2 or 3 things at the same time muddies the experiment and opens the door to all sorts of fallacial reasoning.

- Ego gets in the way. Things like confirmation bias and ‘avoiding failure’ prevent humans from seeing things objectively. And, often, failure means missing KPIs or OKRs that lead to promotions and a higher sense of self-worth.

- There’s no peer review in corporate innovation. Peer review (i.e. inviting colleagues to critique, objectively, the methods and theories of the working group) isn’t how corporate innovation teams are set up. Crossing ‘silos’ to engage people with no context is difficult and, even if it’s possible, we end up with ‘inventor bias’ where the working team asks peers leading questions like, “You would like it if this was invented, wouldn’t you?”

Hypothesis-led innovation is a robust process – well, it’s the best we’ve got. The foundations of science are based upon it. It’s just that a commercially-oriented culture where teams are measuring profit as an outcome, as opposed to an academic one which is, “Where do I get my next grant from.” makes it much more difficult, but not impossible, to do well.

Research-led innovation

While hypothesis-led testing is an appropriate, robust, and ‘active’ way to make progress in innovation, there is an alternative and that’s being ‘research-led’. The difference is subtle, but absolute.

In hypothesis-led innovation, teams rally around a theory and get to work quickly, often playing with tech and outputs to move towards validation or invalidation of their hypothesis. In research-led innovation the ‘act of working’ starts from observation, not action.

Research-led innovation begins with generative research that is grounded in behaviour, not attitudes. It requires an agreement between the working team that observing is valuable and a collective trust that it will lead to an positive outcome. It requires a deep sense of curiosity and open-mindedness about those outcomes because it may be that the team doesn’t learn what they expect to learn but, quite critically, they always learn something. That something, even if it describes a path that the team can’t follow, is valuable.

Research-led innovation requires a few things to do well:

- A definition of a space: this might be a type of customer or non-customer. It may be a particular activity, or a particular environment or domain. Putting a boundary around this is important for constraining the scope of observation – quite simply, it’s impossible to observe infinity.

- Excellent and diverse research skills: Experienced researchers who have years of practice recording unbiased actions, conversations, and other human behavioural factors is critical. This sort of contextual inquiry goes beyond non-generative research, like usability testing, and lives in the realm of ‘recording the unconscious.’ There are very few people who do this well.

- An opportunity mindset. A thing that most money-spending organisations have trouble with because the ROI isn’t clear, and often isn’t for sometime. Again, it requires an understanding that generative research *always* produces results, whether the funding team likes those results or not.

I’ve spent time sitting and watching people shop in supermarkets, drive trucks, operate in call centres, all without doing anything but watching and asking a few open-ended questions like, “I saw you just took that bread off the shelf, why that bread?”

The giant leap we all want to make comes from listening first, not acting.

Noticing the every day is an art and a skill. It requires patience, curiosity and faith – all traits that you won’t see on a job ad for innovation teams that are looking for ‘fast-paced, exciting, entrepreneurial qualities in their people. And therein lies the crux of the problem – the perceived value of observation, just as our First Nations People have done for 60,000 years is under-valued by the western and start-up mindset of acting before observing. Hence, we return to the comfort zone of hypothesis-led innovation that’s driven western science for hundreds of years.

The giant leap requires patience, not ‘action’

Innovation has a ‘brand’ – new, exciting, untetherable and exploratory. Steve Jobs in all black, secret missions to unlock world-altering technology and systems on the world. But its brand is, in itself, its own problem. Because what innovation is really about is change. What innovation goes looking for is ‘the giant leap’ – something that’s truly game-changing for the industry or problem space within which we’re operating. It’s got confirmation bias baked in – if the leap isn’t giant, then it’s not innovation.

But, to make a giant leap, don’t we need to exert lots of energy?

And that’s where we’re going wrong because the way to get giant leaps is, in fact, counter-intuitive. What the giant leap needs is patience. To stop, observe, listen, understand, first. It’s not sexy, energetic, or exciting. But, it’s only after this perceived ‘passive’ activity that we can act. Precisely and swiftly. To go from A, directly to G.

Until we begin to take a listening-first approach, those giant leaps aren’t likely to come. Instead, we’ll either end up with small, incremental change (which isn’t a bad thing but often not the goals of innovation labs), or, the one I’ve experienced in three different teams: no change at all and a growing distrust of the value of ‘innovation labs’ at all.