There are lots of things I love about academics. The passion they have for their work is one of them. So to is their understanding that exploration for explorations’ sake is a useful and valuable human endeavour. Solving chunky problems that others have never before solved, combined with passion and exploration is what helps to move us forward as a species – better health, better living conditions, better overall.

Academics don’t need to be founders: taking research to market doesn’t mean ending an academic career

But, their passion for exploration means that something else has to give. My experience of working in early-stage research commercialisation projects has shown that academics view making money from their work as ‘impure’. Commercialising research turns ‘exploration for explorations’ sake’ into ‘exploration for profit’.

Most academics I’ve known are not motivated by money, but by status and prestige – a tenure position, more grant funding, more published papers. That’s not a bad thing. We need those motivators. But I’ve also seen how commercialising an academic’s work has scaled their impact and affected hundreds and thousands of lives for the better. It’s not difficult, in fact, academics have already done the hard work.

Does the thing I discovered solve a problem for somebody?

The thing about academic research is that curiosity leads to knowledge and, often, knowledge leads to a solution that no one asked for. In design, we work the opposite way – understand the problem then find a solution to fit the problem. Neither way is better than another, the important thing is the match – does the thing I discovered solve a problem for someone?

Problem → Solution can easily also be Solution → Problem

The most critical part of this step for academics and researchers is understanding the difference between real-world solution and lab-tested solution.

Pharmaceutical research, and other regulated industries already has a defined pathway to market (trials → approvals → market) so I won’t cover that here. The type of academic discovery I’m talking about is non-pharmaceutical. And, from years of experience, I’ve seen first-hand that trialling a solution in a controlled environment (like a lab), and an uncontrolled environment, yields different results.

It’s important to understand if the product or service that’s been discovered from research actually solves a problem and for whom. It’s most important to be as specific as one can about the who → problem → solution as possible. The who bit, in commercial language, defines the ‘market’.

Are there enough people willing to pay for their problem to go away?

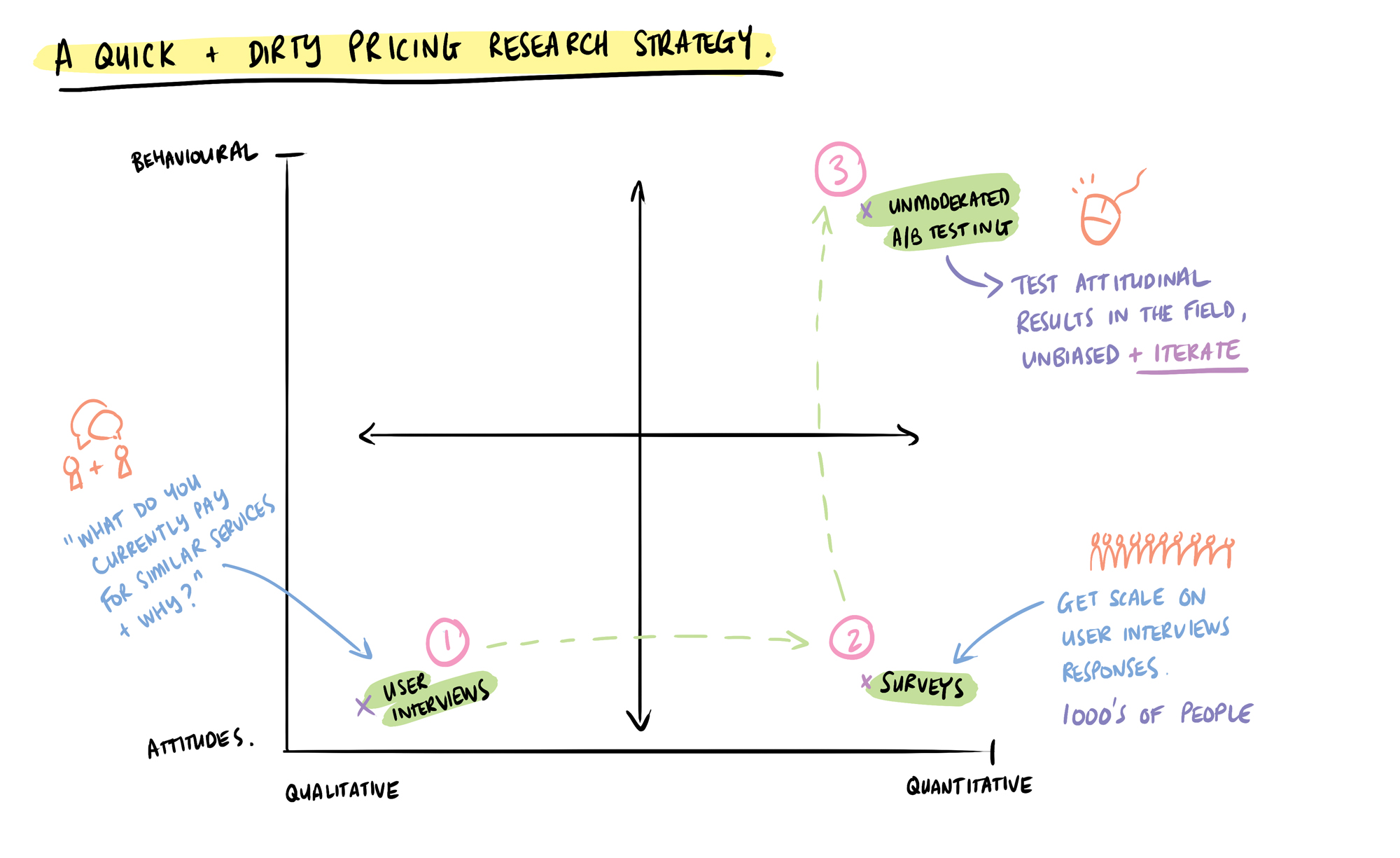

If an academic’s solution tests well for a particular cohort or cohorts in the real world, the next step is really quite simple and rather scientific. It involves answering two questions:

- Who can benefit from this solution?

- How much are they willing to pay for their problem to go away?

This is what designers and product people call “Commercial Research” and/or honing in on “Product/Market” fit.

Every founder and/or academic thinks that their work is the bees knees, if they didn’t they’d begin to question why they’ve spent (sometimes) their entire lives working on this thing that isn’t very good. And so here’s where a healthy dose of external parties can help – to validate or invalidate the assumptions made by those who believe in their work. It’s essentially peer review – and all academics know how useful that is.

How many is enough?

The ‘enough’ question (i.e are there enough people willing to pay enough for my solution), in the context of commercialising research, is typically considered at two levels:

- Will I earn enough money to sustain the product over time?

- Will I earn enough money to grow and make the product better, over time?

As designers and commercially-oriented people, we tend to err towards the second one – mainly because, when things become products, competitors exist and a business wants to remain competitive. To do that, one needs enough money to change and evolve over time.

What’s the optimal ‘business model’?

If it turns out that there are enough people who are willing to pay for their problem to go away, the next question becomes about the mechanics of how that might work. Digital products have all sorts of models: subscriptions, one-off payments etc, and I won’t go into that detail here, but this isn’t a difficult problem to solve with what academics do best – that’s right, more research.

The business model that a product begins with often changes and morphs as the solution is used – what’s good fuel for the child isn’t necessarily good fuel for the adult. And so the ‘optimal’ business model is an iterative process. It requires constant checking and validation of previous assumptions up to this point, an understanding of what competitors may be up to, and an eye on the future.

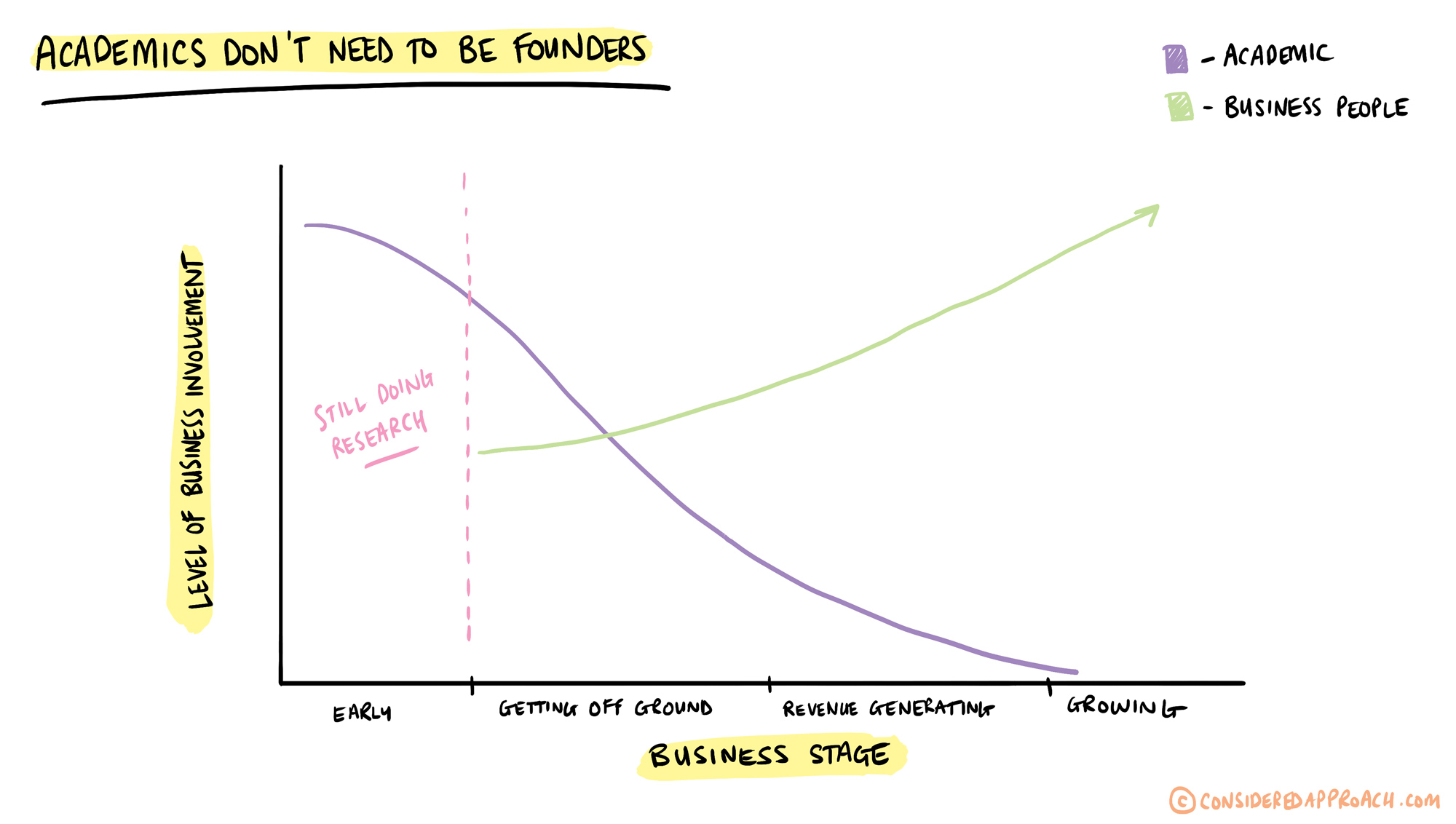

But, by this time – the research has been commercialised and it starts to live a life of its own; just like any ‘normal’ business: building teams, salespeople, staff, revenue/profit/expenses etc are all part and parcel of the transition of research to commercialised research. In my experience, this is the bit that scares academics who, primarily, want to keep being academics.

Academics don’t need to become founders

The pathway to commercialising research can seem daunting for academics who, in the end, just want to keep being academics. But academics very rarely work alone in their research. They surround themselves with professors, graduates, and other researchers who help them make better work and think through their work more deeply.

Commercialising research, just like doing normal academic research, works best with a team around the founding researcher. A good designer and good product manager can be an academic’s key to unlocking their research benefit to the wider world and the academic can keep doing what academics do best – to use their curiosity and passion for exploration: to find out the next thing that will improve the way we humans be humans.