One of the core tenants of human-centred design is, well, the human-centred bit. What this is supposed to mean is that we – professional designers (and their teams) – create products, services, and interventions that consider the genuine needs and wants of the humans whose lives we’re trying to improve. And then actually improve them.

Bound by the rules of capitalism, designers, on the most part, have been engaged in a decades-long advocacy struggle with those who want more efficient and profitable businesses to, please, consider the people they’re making products and services for.

Over those decades, designers have attempted to develop tools and frameworks to help make their case more concrete, or present it in a language that the decision makers of businesses (whose primary concern is the shareholder), understand. Driven by the (perhaps fallacious) idea that what’s good for the user is good for the business, designers start at one end of the spectrum – absolute advocacy for the interests of those who use the products and services that are being provided by the business. The business owners start at the other – the most efficient way to maximise profit, reduce cost for shareholders, and deliver on what is often a pre-defined strategy.

Most designers know that the best way forward through any conflict is through compromise and so, over time, that’s what we’ve done.

Let’s for a moment, imagine a HCD Utopia

When I hear my peers describes their ‘teams’, I hear stories or various articulations of ‘the three-legged stool’. i.e. they largely consists of three primary roles – Designer, Product Manager, Engineer/s. This is currently ‘normal’ in technology-focussed teams. These technology-led cultures mostly consider this ‘multi-disciplinary’ and, most recently, our model of this is ‘maturing’ to include other business roles like Sales, Marketing, Subject Matter Experts and so on.

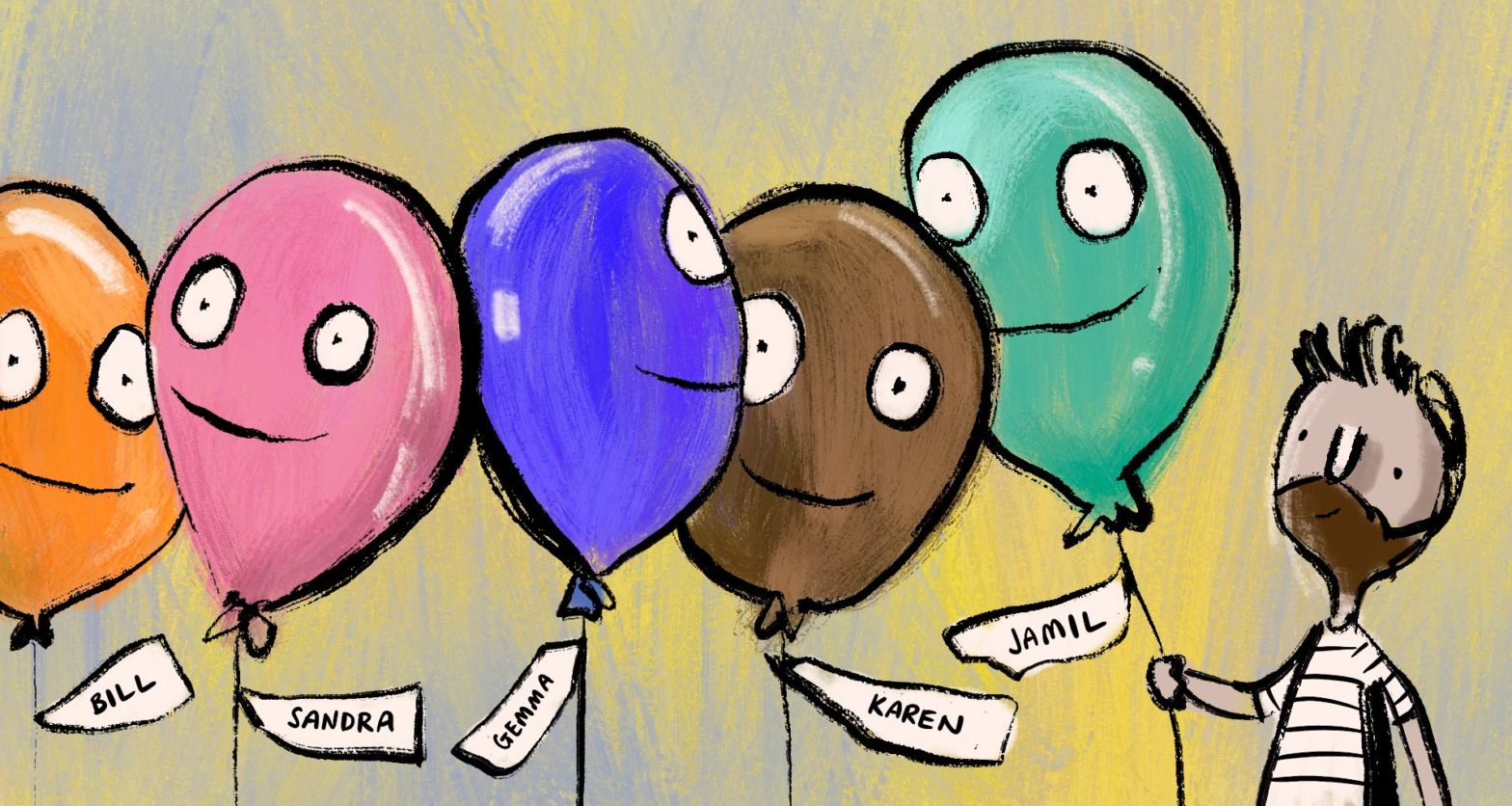

But, I don’t know any team or business today that employs the people for whom they’re designing; yeah, that’s right, employing the user. Not just employs them, but makes them equal and integrated members of that team. Even writing that sentence feels extremely radical. And, by employ, I don’t mean a token $60 for filling out a survey. I mean a long-term, project-length commitment to contributing to the design process – to literally be the human/s in the centre of the design process. Designers, Product Managers, and Engineers as peers to those whose lives we are trying to affect. What would that world be like?

What if users were working and being paid alongside us, as equals?

Guided by principles like, “No solution for us, without us”, the idea of true HCD is co-design (aka participatory design): absolute user integration into the design process. Not that designers and other technology professionals are somehow more superior or powerful in the process. What I’m talking about is true equality. It’s difficult for us to imagine this utopia because it so rarely happens.

In a perfect world, having the communities for whom we are designing be an integral, long-term, and consistent part of the design process is what human-centred design needs and, at the moment, very rarely gets.

What’s the next best thing to co-design?

Employing the humans for whom we are designing is nowhere near the Overton window right now. So, as good designers do, we’ve decided to take a compromising step toward the middle – a lean (and therefore cost-effective) approach to involving users in the design process. After all, employing the people we design for is comparatively expensive to asking them to contribute on an ad-hoc basis. We, as a profession, are currently satisfied with the ad-hoc basis of user input.

Getting regular and direct access to users in this lightweight way is still seen as ‘expensive’, ‘time-consuming’, and ‘difficult’.

Here’s where we currently are: The three-legged stool (all of which earn upwards of 150k/year each), give ‘incentives’ to users to participate in the design process in a lightweight way. Research methods like focus groups, surveys and so on, mostly at the beginning of the design process, is the ‘normal’ way. Teams offer things like $50 – $100 cash or vouchers to the people who’s information and context are critical to the success of the solution (and therefore revenue of the business). Even this model, as basic as it is, still has it’s difficulties. Some businesses have made this approach part of their day-to-day – they have dedicated budget for incentives and process like ResearchOps. But, a lot of the time, getting regular and direct access to users in this lightweight way is still seen as ‘expensive’, ‘time-consuming’, and ‘difficult’.

And so we’re currently in a situation where two things are true:

- It’s still largely considered ‘expensive’ (both in time and money) to get ad-hoc input from the people and communities in which we’re paid to intervene and, hopefully, improve for shared value.

- Driven by ideas like Design Thinking, most organisations have become comfortable with non-iterative, linear processes of “design & release” product development.

By combining these two things, we’re left with a process that masquerades as human-centered design but is so far removed from the principles of good quality co-design such that it becomes, in the most literal sense, unjust and potentially harmful to those communities that we believe we’re trying to help.

And then, there are personas

Having said all of that, I believe that most designers (and product teams), at their core, want to genuinely make things better in the world. And so, in a valiant effort to be more human-centred but still deliver increased profit and reduced cost to businesses, we’ve continued to try to find a better middle ground: How might we ensure that the team making decisions in their high-rise meeting rooms of the company offices (or homes), don’t lose sight of the human impact of the decisions they’re making; all without spending more money and time than we already had approved at the start of the financial year. Enter the persona.

At their core, personas are averages. (I’ve always hated them). They were the design community’s attempt to help non-designers in the team and business empathise with the people whose lives they were attempting to change without going to the cost of paying individuals, regularly, for their input.

We’ve created a habit of engaging the people we’re designing for mostly at the ‘start’ of the design process. We seek to understand their behaviours, needs, motivations and context through various research methods. The law of diminishing returns state we probably need 6-8 people. At $50 a pop, that’s about $300. Business budgets can typically swallow that. It’s the first part of the double-diamond, right? That’s easy to sell to the executive. A required step in a linear process. Approved.

And then, with that very limited set of information, we abstract our findings enough to create averages. We give them kitchy and further abstract labels like, “The dreamer” or “The planner”. We use age ranges or other general characteristics (derived from Marketing) like, 30-60 year old mother of two. We make nice little posters and present them to the business and say, “Here, here’s what your $300 got you. Valuable, right? Can we have more budget next time?”

And, in the moment, it feels good. The outlay has been minimal and we feel like we understand the people we’re about to design for. Then, with no additional input, we typically create solutions in our offices, in isolation from those people who gave us the critical information about their lives. We may test them but, increasingly, our product delivery culture has become one of shipping first and ‘testing in real life’ – move fast and break things, right? Well, that works if there’s time to iterate in real life, too, but that’s almost never the case. And, when you can ship to 2 billion people overnight, it’s outright dangerous.

But, it’s better than no user input at all, right?

Ah. Well. No. And here’s why:

- By designing for averages, we create average design – solutions that don’t really solve anyone’s problem and, because of this, often create more problems.

- Our product design culture is typically not one of build, measure, learn. It’s one of build, build, build. Businesses still think they require certainty – a top-down plan that can be communicated and set expectations with a board – so roadmaps are typically drawn months in advance, with ‘features’ already prescribed, and very little flex built in for teams to release something, learn something, and adapt (which was what agile was supposed to be for, by the way). It’s antithetical to the complex adaptive system that is the human/technology relationship.

- Persona documents are very rarely (if ever) updated. They look and feel complete and factual. If the designer can abstract the groups enough they feel as though they cover ‘all of our target market’. New research often happens at a feature-level once the initial research is complete but that’s very rarely captured company-wide and shared across all design teams so we all end up working off bad, abstract, and old information.

- Most worryingly, it’s changing our practitioners’ definition of what good human-centred design looks like – it’s now OK, in fact, ‘progressive’ to work in this way. New designers are watching experienced designers work in this way and calibrating their levels of what good HCD looks like. Research upfront, ideate, plan, then build, build, build until the end of the financial year and the budget’s gone. That’s not OK.

Complex Adaptive Systems

The thing with designing tools and services for humans is that the relationship between humans and their environment is a complex adaptive system. First we design the tools, then the tools design us. This means that the lean, linear, lightweight processes that currently characterises ‘progressive’ HCD in most larger organisations intervene in systems in ways that no human, no matter how much planning and research we do, can predict. We learn about the human/technology relationship only through interacting with it. It’s a hallmark of complex adaptive systems. It’s ecological, not engineering, and the way we design and intervene in people’s lives is not compatible with this.

What we need from design advocacy isn’t another presentation on the double-diamond methodology or another version of Design Thinking that further advocates for linear ways of thinking about design; we need to recognise and remind one another that the decisions we make about the ways we intervene in people’s lives have intended and unintended consequences every time because that’s the nature of complex adaptive systems. We need to remind each other that it isn’t the behaviour of “The Dreamer” that we’re trying to change – it’s quite literally Bob, Janet, Carlos, Mohammed’s lives we’re changing. It’s my parents. Your kids. Our species, and others we share the planet with. It’s either making a more equal and just world, or it’s doing the opposite.

We need to remind each other that the lives we’re intervening in are my parents. Your kids. Our species, and others we share the planet with. We’re either making a more equal and just world, or we’re doing the opposite.

When we’re dealing with complex adaptive systems, there is no solution, just better or worse. We need to get better at asking ourselves not “Will my boss approve my budget for research?” but “Who might this help, and in the same fell swoop, who might this harm.”

Where does Design go from here?

I don’t think there are definitive answers to this problem we face, to think that there would be is to ignore the same problem I’m describing; there are no solutions at all, only interventions. But, I’m finding that I’m running out of ways to tell some people why they should care about other people. I’m finding myself looking for people who already understand what I’ve been describing: We find each other, we have a great time, and the rest of the world can go to hell. That’s not good.

Maybe the neoliberal power structures that support capitalism will make this impossible at scale. Maybe all I can hope for are small wins. Maybe I can write and change the mind of the next generation of designers who can continue trying to explain to some people why they should care about other people. Maybe it’s about bringing the users for which we design into the team, as long-term, equally paid equals. Nothing else has really worked, has it? Maybe it’s time to try something different.