I’ve had 20 years practice at Design and almost every time I embark on a new project there’s a little voice inside my head that says, “What if we come out of this $10k research project with nothing? What if my toolkit doesn’t work this time?”

That voice is still there despite 20 years of hard evidence that, every time, that investment in research is money well-spent. In fact, every time I finish a project I walk away thinking, “Gee, if I was that client, I’d pay double for that level of insight, de-risk, innovation, etc” – all the things that practitioners know design research is good for.

And so, if even I still have that little voice in my head, with 20 years of direct experience of Design’s value, how can I expect anything but scepticism from a client or executive who’s never seen what design methods can do.

Design as religion

It strikes me that Design is very much like religion. Design, like religion, requires faith – a belief that, if we follow this set of rituals and practices, we will achieve insight salvation; a miraculous understanding of our user/s that will unlock more social and/or financial benefit for the organisation and those for whom it serves.

And, like religion, there are sceptics – design atheists and non-believers. Sometimes, they believe in Engineering. Sometimes, they believe in Product Management. Sometimes, they believe in six sigma management or ‘servant leadership’ which comes in many flavours. They say things like, “I don’t need the fancy colours and clothing of your faith, functional is fine. We’ll just ship faster and learn in real life.” Or, they say, “I already read the sacred texts of your Design religion and we don’t need to hire one of the clergy to perform the sacrament for us. I got this.”

And you know what I’ve learned? Sometimes, they don’t need Design. Sometimes, they have a market or a business that has no competition, or who’s existing service landscape are akin to the holy fires of hell that doing anything slightly better than it was before is good enough for now. You don’t always need the pope to exorcise a devil. Sometimes a bit of garlic around your neck will do just fine.

For years, the devout Christian members of my family have told me that I don’t know what I’m missing by not cultivating a personal relationship with God. And for years I reply, “I’m doing just fine, thanks.” And, I truly believe I am.

Just like we do in Design, religious institutions try to use testimony to show us what life could be like on the other side – if only we were more faithful. So and so was cured of cancer. God gave them a new baby when they asked for one. God protected them on their overseas adventure. Their prayers were answered. Loaves and fishes. Water and wine. The list goes on.

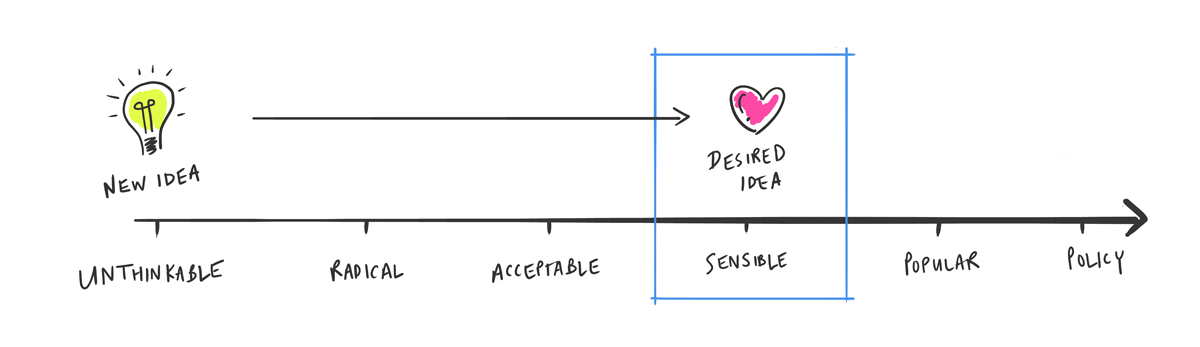

In Design, we write case studies to show the unconverted what they’re missing out on; “Company X unlocked 10x revenue with this one simple design change.” or “Investing in user research gave Company Y a whole new product category.” or “User efficiency went up 10m% because we understood their needs.”

Loaves and Fishes. Water and Wine. Designers perform miracles. Jesus does too.

Design as fact

Those of us in the clergy of this Design religion (lets call ourselves “Professional Designers”) believe we’re offering something special; a version of enlightenment. Those outside the congregation question what the clergy actually does with the pennies they collect from the donation box. The clergy struggle to grow the church and we spend most of our time online talking about how the outside world could be saved, if only they came to church once in a while, or read this sacred text, or repented their sins.

The thing is, no matter what we think of the non-believers, there are some true believers who aren’t one of the clergy – they are non-designers who believe in Design. They are few in number but they are there. I know some! The question is, how did they become that way? What’s their conversion story? Might that be helpful to the Design clergy in evangelising the benefits of Design?

Can I get a witness?

I’ve worked with a lot of non-believers over my time. People who, for one reason or another, thought Design had nothing to offer. But, they read some HBR article at some point and thought, “maybe I’ll give it a try to see what all the fuss is about.” Or, they were working in a highly regulated space and needed the Design process – speaking with users and a report – for some version of due diligence and risk mitigation. There have been, on very few occasions, the ones who need ‘saving’, too; those who fell so far from the grace of God by shipping waste-of-money software and, through the Design process, sought repentance (mostly from their boss/manager).

And you know what? As I’m one of the clergy standing out on the street handing out fliers, I’ll take any non-believer I can get.

What I’ve learned over all these years is that someone needs to ‘experience’ the miracle of Design before they become a devoted follower. You can tell people as many testimonies as you like, but until you feel it – i.e. you go from thinking one thing to thinking another about your audience, or your entire body relaxes as you realise that you’ve de-risked whatever decision you were going to make anyway, or you unlock a market bigger than you ever thought possible – you can’t believe in it. You don’t want to go to Church again if you don’t feel different from it each time.

Give me a shepherd I want to follow

When I was a kid, I was dragged to church weekly by my Mum. It was a really boring Catholic church that simply ‘ticked the boxes’. Read the book. Ding the bell. Recite the prayer. Put coins in the donation. Eat the bread. Ding the bell again. Shake the priests hand on your way out.

I’ve been in design organisations that take a similar approach to their Design work – tick off the steps of the double-diamond (research, report, invent, test, refine etc) and arrive at the end. There is no internal transformation that occurs in both of these scenarios. As a non-believer you’re left thinking, “That was a waste of time. I could’ve done something else with my Sunday morning.”

Why are we surprised if people don’t engage with Design if the clergy makes them yawn or isn’t invested in giving them the transformative experience we know is possible?

One time, I went to my uncle’s pentecostal service. In contrast to the catholic service, this was outrageously lively. There were people speaking in tongues, dancing in the aisles, falling over after being ‘touched by the lord’ and re-born into a new life. Unlike the catholic gospel reading, in the pentecostal equivalent, the pastor was critically analysing the bible, putting it into historical context, drawing lessons from the text, and applying it to the lives we live today. As a 9-year old, I was blown away. I remember thinking, “Woah, if this is Church, maybe I could be into it.”

There are some design teams that do this, too. Teams where the design process is participatory at all levels. The clergy draw on a vast toolkit of design methods and apply them to the problem they’re trying to solve in very targeted ways. They don’t ‘always do focus groups’ or ‘speak to 8+ people’. They don’t always ‘do research’, or write reports, or do ‘divergent thinking followed by convergent thinking’. They are, quite simply, goal-oriented and focussed on giving their client the miracle of Design in whatever format suits the problem they’re trying to solve. It’s those clients that go away changed.

Building a Design Congregration

Building the Design Congregation, as it turns out, works much like evangelical religion. People need people-like-them to have experienced the miracle of Design and ‘spread the word’ that Design Is Good. That it does not judge. That is accepts all who are willing to listen, engage, and approach it with a curious and open mind. That Design is here to save them, and humanity, from the evils of the world like waste. Planting an equivalent of the Gideon’s bible in every corporate office (Design Thinking by those IDEO guys?) ain’t gonna do it. It comes back to designing the the design experience for non-believers.

Those who have experienced the power Design through an internal transformation of their own worldview know that it’s not just faith forevermore, but fact. It’s not mystic creative genius by the anointed few, it’s logic and deduction. Where Design is *unlike* religion is that Design is empirical, evidence-based, collaborative, and iterative. The Designer is not The Pope, but a shepherd. There may need to be some faith to walk into the church for the first time, but once you walk out, you walk out changed. And then you tell others that, maybe next time, they could go – just once – to see what all the fuss is about.

Once I was blind, now I see, or something like that.